A Bleak Look At A Suicidally-Minded Argentinian Existentialist

Greg Gipson Kicks Off Positivity Week at The Republic of Letters!

Dear Republic,

This was supposed to be Positivity Week, but I guess let’s face it: cheer doesn’t come easily to The Republic of Letters. We somehow started by arguing that The Beatles killed music and then, for the first entry in our contest on the “Best Thing you read this year” (All Fours anyone? maybe The Book of Love?), we have a piece about an Argentine existentialist who was tortured in prison and whose best book is called The Suicides. Ah well. Anyway, it’s a strong, sad piece about a writer ROL hasn’t heard of and about how literature sometimes can be a matter of life-and-death. Maybe next week will be Positivity Week?

-ROL

A BLEAK LOOK AT A SUICIDALLY-MINDED ARGENTINIAN EXISTENTIALIST

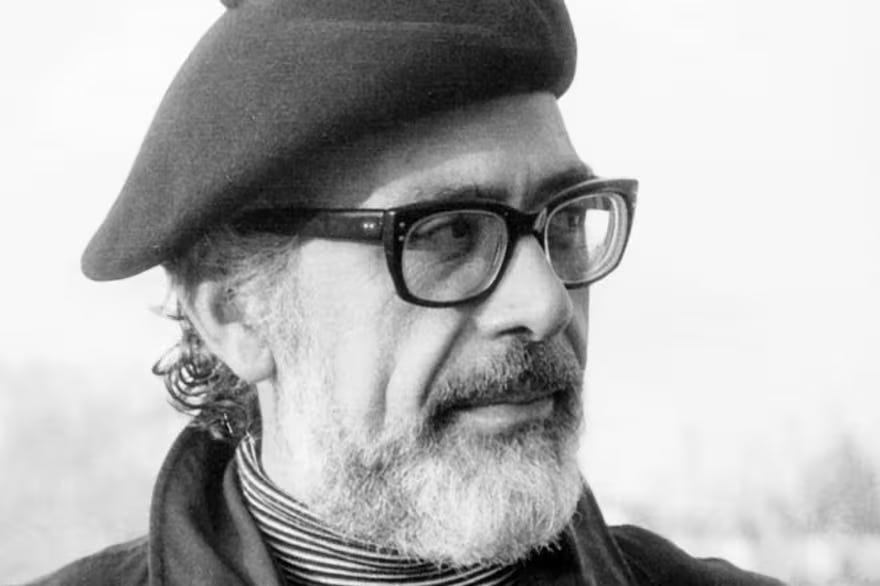

The Suicides, by Antonio Di Benedetto, was published this year in English (NYRB) but written in the 1960s. It is associated with two earlier novels by Di Benedetto: in reverse order, The Silentiary, and Zama. Due to, apparently, the author/critic Juan José Saer’s writing on the subject, they have been long published in a single volume and referred to as the “Trilogy of Expectations.” Zama was made into a film in 2017 by Lucrecia Martel, and is reported to be a favorite of Roberto Bolaño’s. I love Bolaño. I didn’t like Zama. Something about the voice of its narrator, so intimate and creepy, so lonely, just didn’t excite my brain into strong interest, just mere observation. Yet it was, for me, worth reading, the way the grain of sand is worth being troubled by — not for the oyster, but for the diver. I don’t know anything about Di Benedetto (who, despite the name, was Argentinean; as with many people of that country his family was Italian, i.e., from somewhere else), save what the introductions of these NYRB editions tell me, and a little bit online. I don’t read Spanish. I have to assume it is true that his reputation in his lifetime was small and has steadily grown particularly after his death (and presumably after Bolaño’s comment became known). In some ways he exemplifies the NYRB project of rescuing worthy authors who either fell off the map or never quite made it, due to whatever institutional forces or personal foibles. Di Benedetto, on the evidence of this “trilogy,” definitely merited rescue, although his austere and sometimes cryptic way of writing also makes it clear why more florid, more visibly passionate, and more telegraphically political writers might have been easier for both a Spanish-reading and then English-translation public to admire. It also might have simply been English-language publishers shrugging: “We’ve got Borges. What do we need with another Argentinian?”

All three books are quite obviously concerned with existentialist-framed themes, and the efforts of modern people to seek meaning in the miasma of lost, broken narratives and dissolute remnants of morality in the wake of God’s death (or whichever other massive source of disillusionment you want to reference). Zama’s narrator is perpetually out of money, despite being a government official in the colonial government. He is always fretfully checking the progress of ships bringing gold, cadging meals, taking loans, feeling ashamed of his situation and enraged at the treatment he receives. He moons for his family, who are far away and never return in the narrative’s time frame. Significantly, the narrator is native-born though European, and is discriminated against for not having come from Europe itself. Much of this is muted, at odd angles: the narrator is an obviously unreliable point of view, and time skips around at several points. It’s a short novel, trembling and astir like a small, anxious dog.

The Silentiary, written in the ’50s, is set in the then-present in an unidentified (“a city in Latin America as of the late postwar era”) place where the nameless narrator lives with his mother, dates, marries, and has a child with a woman he is settling for because he actually wanted her friend, is led into grandiosity by his mysterious friend Bessarion, and aspires to write a book, but is perennially blocked from doing so by the noise of city life. Like the hero of Zama, this man is feckless, and trapped in the rut of his refusal to act. There is, now that I think of it, more than a little in common with Pessoa the man and Pessoa the writer of The Book of Disquiet. “My conviction that I can write is not based on any contact whatsoever with writers, only with books,” he says early on, but, at the same time, “I would repeat the first distinct sentences of the work to myself. They lived up to all my hopes. In reality I resisted giving myself over to the book. Soon I was hard at work getting it to slip through the cracks.”

For a book primarily about silence, The Silentiary is surprisingly also focused on time and the existential loneliness of living fully aware and awake — something Camus did write about but which I can’t precisely recall and haven’t looked up for this essay because The Suicides persuaded me that I need to return to Camus to read The Fall and The Myth of Sisyphus, and reminded me of how ubiquitous and urgent Camus seemed even as recently as the ’90s, when The First Man came out to acclaim (and deserved it). Before staring at screens all day and grumbling about our lack of experiential interaction, we used to take seriously the idea that living an “engaged” life was a way to find meaning in a world that offered much distraction and little sustenance. Maybe that was in part the living memory of World War II, maybe it was the lack of the full level of distraction that the Internet has “given” us. But Camus feels forgotten to me — living, now, in my suburban home with my midlife concerns. I hope people are still whispering about him even if The Stranger has become slightly too well-known. (And also I hope that someone will get around to doing a new translation of The Fall because Covid gave us a new Plague and we should stop reading French writers in Britishized translations, full stop. But that’s another story.)

The Silentiary is an inferior book to The Suicides but still makes plain the full range of the existential dilemma underlying all three of the books. I should say that existentialism, for all its obvious flaws in execution, has always seemed, like the Buddhist conception of existence tied to suffering arising from desire, to be, plainly and forthrightly, important/necessary/practical (take your pick as to which is the most salient). For me, the most central image of The Silentiary is not the elaborate descriptions of the noises of the auto shop, machine shop, lumber mill, motorcycles, and other noisy obstacles that obstruct and finally make mad our narrator. No, the most provocative thing is his revelation that time is passing and is forever:

In the contemplative hours of adolescence, the instants made themselves visible to me as thin circular wafers or lozenges with surfaces of polished gold. Time soaked through them, one by one, but their continuous procession never ended. … I’ve been living from moment to moment ever since, but I’ve never again seen one of those gilded lozenges, and from the next instant the world delivers to me I expect nothing but its burden of adversity.

The Suicides opens with a line from Camus, about how any sane man has contemplated suicide. It’s from The Myth of Sisyphus, one of Camus’ essays about “absurdism” and the way it does not justify suicide. I’m not going to summarize it; the “absurd” he refers to is the lack of inherent meaning in human existence. (I think. Also, why should we expect inherent meaning? etc.) The novel’s nameless narrator is a reporter for a news agency who is researching recent cases of suicide in order to draft an article. He is surrounded by macabre-minded women who help him with the research, one by providing him notes on famous suicides and another who photographs eccentric family members of the suicides. The narrator explicitly references the epigram “The question isn’t why I would kill myself. It’s why I wouldn’t kill myself.” With a lot of random dread and wariness, the novel proceeds with its “investigation” while the narrator unravels his romantic relationship and takes up with one of the other women, who intends to kill herself — as we realize gradually and then all of a sudden. “She suffered from a terror of not being one individual: She was everyone else.”

The plot isn’t the reason The Suicides is the best book I’ve read in the last year. The language of it, the weird elliptical cycles, was definitely the appeal. On the one hand “I move forward, into the calm darkness” and on the other “When someone does something with passion, the people around him go along with it, even against their will” is enough to give you whiplash. The narrator resists; he doesn’t want to kill himself, he does want to kill himself, he does not think he must, he recognizes that it is the only reasonable thing to do. He is worried because: “My death wish is also a wish to kill others. I can’t kill them, at least not all of them: if I do away with myself, they’ll no longer exist for me.”

The novel posits that Camus is wrong, and that not only is the only rational response of humans in this world to consider suicide, but that they actually should do it. The novel ends ambivalently. Probably this says more about my mental state in the present day than it does the success of this novel, which will no doubt be pilloried in the comments as too woke or too anti-woke or whatever stupid and utterly besides-the-point thing we are shoehorning into every discussion on this cursed forum today.But it persuaded me. I have been wasting my life, frittering away those golden lozenges. My father dying, slowly then very suddenly, while I proceeded as if many more orderly, golden lozenges waited for us, persuaded me. Lost really is lost. I have been wasting my life, frittering away those instants. My mediocre existence of value to no one persuaded me. I have been putting off my sole ethical obligation in this world — to stop fucking around and get on with it — and cannot any longer.

I will check in with Camus and see if he is persuasive. I will read more poetry, and I will write something for myself and myself only for the first time in a long time. And because I am a coward I will end up moving forward, into the calm darkness, even against my will, knowing I have failed.

Di Benedetto, by the way, did not kill himself. He wrote the novel as his home was beginning its slide into the authoritarian nightmare for which it has been so famous in our lifetimes (read Kamchatka, or Dead Girls or Rodolfo Walsh, if you can find anything in print). He was arrested in 1976, spent a year in prison, was tortured, and seems to have come close to execution (rather like his model and proto-existentialist, Dostoevsky, but after he wrote his books) but was released and lived on until 1986.

Kill your darlings, indeed.

Greg Gipson remains at present a pseudonymous lurker on Substack. He (long ago) published at Grist.org and The Believer but has largely marinated himself in books and thoughts about books and ideas for books (as well as some other notable experiences) for the last few decades, never quite starting the grill. As this essay describes he hopes to change that, at least a little. In his day job he writes, but not that kind of writing.

A strong start to the Best Thing series.

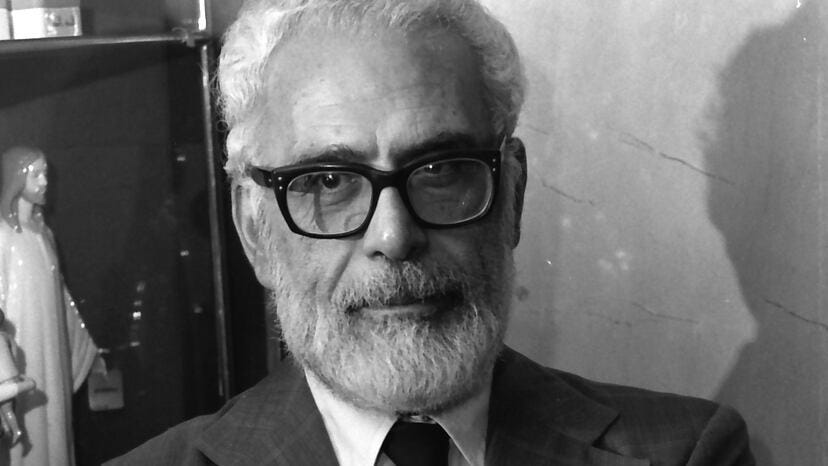

What is it about Camus and Argentinian writers? I wasn’t familiar with di Benedetto, but your discussion of his writing reminded me just a little of his slightly older contemporary, Ernesto Sábato (also of Italian ancestry), who published a very Camus-like little novel called The Tunnel in 1950. You might take a look at it if you haven’t already, it’s only 138pp. And it was Camus who recommended it for publication to his publisher (an early translation called it The Outsider).

If that appeals to you, then there’s also Sábato’s big novel, On Heroes and Tombs, with its novel within the novel, a long section called Report on the Blind, about how the blind secretly control the world.

Many years later, Sábato headed up the commission that investigated the “disappeared” during Argentina’s authoritarian period.

(For some reason, your description of the “macabre-minded women” the narrator works with brought to mind Ginger Snaps, a little horror movie that opens with what appear to be lurid crime photos of the two main characters, sisters Brigitte and Ginger, who appear to have killed themselves, then we learn that posing and photographing themselves like that is their hobby.)

I didn't find this piece bleak at all, certainly not this part: "I have been wasting my life, frittering away those golden lozenges. My father dying, slowly then very suddenly, while I proceeded as if many more orderly, golden lozenges waited for us, persuaded me. Lost really is lost. I have been wasting my life, frittering away those instants. My mediocre existence of value to no one persuaded me. I have been putting off my sole ethical obligation in this world — to stop fucking around and get on with it — and cannot any longer." I found it inspiring. I'd heard of Di Benedetto thanks to the Beyond the Zero podcast episode, in which his translator, Esther Allen, was interviewed. This piece piqued my interest further.

Here's the link to the podcast: https://open.spotify.com/episode/6prPQ6cqtWHoDxLRb4DeYb?si=1bzxJBZWTvao4aFeW2XpnQ