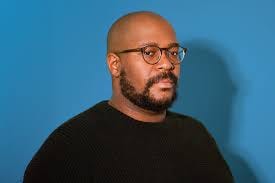

Brandon Taylor Answers All Possible Questions

In Which We Introduce Our Interview Series

Dear Republic,

Brandon Taylor is one of the very most interesting writers around, and it’s an honor to feature him as we inaugurate The Republic of Letters’ interview series. Brandon’s writing includes the novels Real Life and The Late Americans and the short story collection Filthy Animals. His Substack is

. And, oh by the way, he thinks you are a ‘dweeby contrarian.’-The Editor

BRANDON TAYLOR ANSWERS ALL POSSIBLE QUESTIONS

1.You started off in science, doing a graduate biochemistry program at Wisconsin. You wrote in an essay: “Science was saying nothing because I was tired of being corrected about the particulars of my own experience. Science was being told that I should consider moving to the other side of town where more black people live.” I think you covered a lot of this in Real Life, but can you explain more what you mean? Are you talking about the specific social experience of being the only black person in an all-white program? Or are you talking about something specific to the environment of science in American institutional settings?

I was speaking about my experience with Science academia as a Ph.D. student, but that kind of life is itself just another form of life within an institution, and as such, the statements in the essay could also be made about any other kind of institution. One could sub in America even for Science.

As for what I meant, I had a lot of people (many of whom meant well, some of whom did not) trying to get me to compartmentalize my emotions and my personal difficulties with Madison, Wisconsin, and to give myself over to the cool and distant objectivity of science, as though science were itself not a deeply subjective field. Meanwhile, I was having to deal with the people in Science, who felt that their ideas about society were objective.

That essay (lyric essay?) came out of frustrations that felt very specific and particular at the time as having to do with Science because I was being trained to be an American scientist. Looking back at the piece, though, I recognize the broad contours of any sort of institutional life in this country.

2.What was your path from there? What went into the decision (or maybe it was a succession of micro-decisions) to leave science for writing? I assume that must have been a nerve-racking decision, like in terms of imagining your own financial future?

For most of my life, my goal and ambition was to be a neurosurgeon. So I studied science really intensively. I took science electives in high school. As an undergraduate, I studied chemistry, and I was pre-med for the first half of college. But then I got sick of other pre-meds, and decided I didn’t want to be a doctor after all. I couldn’t see myself dealing with those people for eight, ten more years of education and training.

I decided to pursue research, specifically regenerative biology, so I went to get a Ph.D. in Biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which was the best biochemistry program in the nation. I had taken some creative writing classes as an undergrad, but I never really saw it as a path for me because I was so focused on science, and also I had basically never read a contemporary novel in my life outside of romance novels. I had this idea that books were things from the before-time. I didn’t really connect the little stories I was writing with the idea that there was a publishing industry out there that would publish books. I had no idea how books were made.

My first year in Madison, I didn’t write at all, which was misery because I was deeply unhappy in my program. Grad school is hard and I had no coping skills. On an off-chance, I saw a Meet-Up group for writers and I thought, well, I was happy when I was writing stories in undergrad, so maybe I’ll do that and it will help me. I started attending weekly workshops with this group of other writers.

Then, for various reasons I won’t get into, I decided maybe I should look for an alternative path, like what would I do if I couldn’t do science. On my way home from a particularly bad day in lab, I stopped by the post office and mailed some stories to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Then sent in the application and kind of forgot about it.

When I got accepted, I had this choice between the path I’d always wanted and known and this totally unknown thing. And ended up choosing writing. Which I thought was very out of character for me. But when I look back, it was maybe very in character. I had this way of kind of blowing up my life in various ways and remaking myself, choosing the odd path. Even though I mostly considered myself pretty safe and conventional.

3.How would you assess your experience in MFA-land? Almost everybody I've ever talked to really bashes it. From outside, it seems to have worked out well for you — and done what's it supposed to, in terms of creating a pathway towards a writing career. But maybe it feels very different on the inside?

I am actually grateful that I have an opportunity to correct the record on this because I think people have the wrong idea about my path. When I applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I had already written several really viral essays. I was an editor for a literary magazine (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading) and I’d published like a dozen stories or something like that. I was on my second agent before I even printed out those stories and mailed them in.

By the time I arrived for my first week of class at Iowa, I already had a new literary agent, two finished manuscripts, and a really clear sense of what I wanted from the program (I didn’t get it, lol). I never workshopped a single word of my novel. Or most of the stories in my collection Filthy Animals. Not a word. I sold my books before the start of my second semester in attendance. And I was the fourth person at that program in my cohort to get a book deal. Two people came in with deals.

I got accepted with fellowships to Tin House’s summer workshop and Lambda’s Queer Retreat before I even got my acceptance email from Iowa. I say all of that to say that before I even matriculated, before I even updated my bio to say that I would be attending that program, I had already done a lot of work to create my own pathway to a successful writing career.

While living in the MIDWEST, in Madison, not even Chicago or a big cultural hub. That was years of grinding it out. Writing essays. Publishing stories in little mags that meant something to me. Reading for magazines. Editing for magazines (for free, mind you). Sending love letters to writers I admired and loved. Building a real sense of literary community via the internet because I was so lonely and desperate to find other people who loved words. I didn’t know shit about the publishing industry. I just loved writing and pursued it aggressively, like any other field of interest. My success if it’s down to anything is down to that. Those years of passion and community building. It’s not about what school I went to. People reached out to read my first novel because they’d been following me since I started posting bored selfies of me at a microscope, not because I went to Iowa.

As for my experience there, I was miserable. I went in thinking I would find the people who would help me understand my work and myself. I went in thinking that I would finally feel at home. But it wasn’t that. It’s nobody’s fault. But it was a very hard time for me. It was really brutal. I struggled a great deal and wanted to quit my first semester. I am sure there are some people who wished I had.

I think people have this idea that Iowa or the MFA in general is some place where people get rubber-stamped and sent out into the world, but that is not true. I will say that my teachers were not particularly interested in me or my work. They exerted very little pressure one way or the other, good or bad, positive or negative. It truly was a place of almost benign (sometimes hostile) indifference from my teachers. But the real gift of it was that as a program, it offered me health insurance, time and space to write. Time to figure it out on my own. Which in retrospect, I recognize as being the exact best thing for me. I maybe would have turned out worse had I been mentored.

But yeah, while I was going through it, I was miserable. It was ugly. And I wouldn’t do it again.

4.And then you become a successful writer. Can you talk about how that happened?

Well, again, as I said above, I think part of the reception of Real Life had to do with the fact that I was slightly more visible than the average debut novelist who emerges from an MFA program. People already kind of knew my name and would maybe look for the book.

It also helped that the novel wasn’t the first thing I had ever published in my life. I had been in several anthologies by that point. I had written a lot of online pieces. I think the book really rose on a tide that was already in motion.

The pandemic happened, and I got very ill during it. But then the book was a finalist for the Booker Prize that year and that made it even more visible. I didn’t get…any awards attention in America. I still get very little awards attention in America, which I think has something to do with my visibility and people’s identification of me with the internet and maybe I laugh too much online. Anyway, the awards helped that book find a broader audience. Which itself was a credential.

Then during the uprisings of 2020 around BLM and George Floyd, a lot of editors started reaching out to me because I was a black gay writer who had written a book about a black gay man who sometimes gets micro-aggressed, and they wanted me to write all these essays about my trauma and the state of America, and I very quickly peaced out from all that stuff because I had no interest in becoming a race profiteer. And I think if I had made a different choice, I’d be very famous right now, but a worse writer.

Anyway, the short answer is that part of the success of Real Life is that yes it came out and got good reviews, but more to the point, that book got a wave of attention that I would not have gotten if I hadn’t already established myself as a kind of guy about town. There were other debut books that came out the week before mine or even the same week—really good books—that didn’t get a fraction of the attention my book got. And it’s not because my book is soooooo much better. Those books got good reviews too. So some of that is luck. Some of that is, have you done pre-work, too, of building a community, a “platform,” whatever. So that the book gets more eyeballs. Then maybe it’s up to the quality, you know. Or just the arbitrariness of taste and luck.

5.How has your life changed since being a successful writer?

I don’t have a sick knot in my stomach all of the time worrying about food. Or about rent. I can pay my bills. The downside is that I have more haters and sometimes people create elaborate fictions about me and project them onto me. But the biggest change has been material. The quiet that you get from not having the constant chirping in the back of your mind of where your food will come from. How will you bridge the summer when your fellowship ends. Sending out endless job applications to no response.

When my first book published, I had like, zero dollars in my bank account. When I went to one of the hotels on book tour, they wanted to put a charge on my card for the snack bar or whatever. A pre-charge. And it depleted all of my money, and I had to ask a friend for a short loan to be able to eat on that trip. You know. Like I had no dollars, no cents.

But now, I don’t have to worry about money. And I can repay all of the support and kindness that people gave me over the years. I can do it without a second thought. And if a friend asks me for $100, I can send $200 or $300 because I know that they probably need more than they’re asking for. Or I can cover their bills for them for a month so they have breathing room. I myself don’t need more than, like, a sandwich. A nice fountain pen. A camera. I have everything I need, and that material security means I get to offer a little bit of calm to people who need it. Because that calm, that quiet of not having to worry about a bill for a month, like, I never knew it was like that. I want it to be like that for everybody.

So the biggest change is the money. For sure. No question. And to be clear, I am not a millionaire. I’m not a big baller. But I have enough. And I wouldn’t have had that without writing.

6.What I'm most struck by in your writing is the violence that you see undercutting almost every aspect of American social interaction — particularly in institutional settings. Is that a fair depiction of what's charging your writing (or a great deal of your writing)?

More than fair, I think I might have used very similar language myself to describe what’s organizing those first three books. There was a moment in Real Life, where Wallace, the main character, says something like, “friendship was cruelty.” In fact, I almost called that book Cruelty. Certainly, violence organizes many of the stories in Filthy Animals, and I think chapters in The Late Americans often end in a revelation of violence or through violence. I saw (and still see, maybe) violence in everything.

I experienced most social interactions as someone violently trying to usurp my agency. By getting me to agree with them. Or to control my view of things. Or blunting my own experience. I would look around at people interacting or dealing with each other and just see the most hostile, ugly things in every word and gesture. I was confused why other people didn’t see it that way. In part, I was writing to try to understand that gap between how I saw things and how other people did.

7.Here's how I described it in a write-up of Filthy Animals. “On the one hand, there's an effort to see things from the perspective of a loose, easygoing society that’s invested in pushing its limits…and then, on the other, there’s a perspective in which every one of these innocent, exploratory actions is inflected with trauma, and every intrusion into somebody else’s life, no matter the apparent motivation, is in fact a form of dominance and exploitation.” How's that as a summation of some of the central tensions in your writing? And, by the way, what I think is particularly strong in what you do is the roundedness that you have over these questions — your writing is often very angry but without being hortatory or polemical.

I am harrowed by the existence of this write-up. And I am resisting clicking on that link and going to see what else you said, lol. But I think that’s a fair statement about what’s going on in that book. What I will add is that I wrote that book during an intense bout of loneliness, depression, and suicidality. I would tell someone that I was feeling suicidal or feeling frustrated or hurt that someone had said something crazy or racist to me and they would immediately rush in with all this affirming language that was really a negation of my experience. This intensified when my mom died and people kept being like, “Oh that’s so hard, I’m so sorry for your loss, you must be so devastated.” They were almost supplying a script and eradicating any space for my own language and my own expression.

Around the time I started writing the stories in Filthy Animals, I felt very isolated in my feelings. I wanted to create someone who felt exactly as lonely as I did so that there would be someone in the world who wouldn’t try to talk over my feelings or try to coerce me into living. You know, like, when you express suicidal ideation, people wanna talk you down immediately, and for me, that was just invalidating. I have one friend on Earth I talk to when I am suicidal, and we have a pact not to judge each other. To let one another talk about these feelings and to validate how hard living is and to just listen. And it is so…helpful.

That’s why I wrote those stories. Out of this feeling of having been violently coerced into living. The book takes a very suspicious view toward human interaction. When you feel like you’ve been dragged far away from yourself and been made to kneel at someone else’s cross and to speak in their language about your own fucking feelings, yeah, you get mad and angry.

The book is very dubious about the possibility of tenderness or happiness or human connection because at that time, I myself felt very victimized by the “care” I was being shown. And I wanted to illustrate how hollow, false, and stupid those social scripts can be in the face of real human complexity. The mess of human feeling.

8.Where I think somewhat disagree with you is that you seem to adopt a structural view of violence — i.e. that many of these institutions and settings can't help but be violent. That doesn't really accord with my own view of American elite institutions, which may have difficult histories but where — I would contend — people are really genuinely trying. And, if nothing else, I regard theories of structural violence to have a kind of hopelessness and nihilism built into them. But, on the other hand, I haven't had your experience. I haven't been black or queer in liberal institutions. You've said, “I found [liberal academia] to be quite hostile at times. And I found myself among people who had a problem with my blackness or queerness.” When you've had those experiences do you kind of chalk them up to individual bad apples, or to being in an awkward moment in the country's history, or to real insuperable structural violence that undercuts all social interactions in America and is just never going to go away?

I accept your summary of my view here. I do have a structural view of violence. But I would say that it’s more that I experience certain structures as violent. Certain structures in this country simply are hostile to certain groups and certain kinds of people. That is what the hypothetical “good” people in your view are “trying” to ameliorate. I view the violence of these structures and institutions as being inseparable from the make-up of the institutions themselves. Do I believe that someone somewhere a long time ago said, “Let me put a little evil in here for flavor?” No. But do I think that imperfect societies build imperfect systems that generate and propagate harm? Yes.

I do acknowledge that there are people trying, sure, yes, but I would say maybe their trying is not enough. And that sometimes a structure or system must be unraveled and rebuilt with a different set of knowns and conditions. Of course, that system will be imperfect too, but why is that variety of trying (making a new system) so much worse or less worthy than your variety of trying (rehabilitating the old system).

As for the bad apples, man, I don’t know. I once got into an argument with a white guy in a writing group. He wanted me to admit that there was a difference between an old white lady making an assumption about me based on my race and being called a nigger by a skinhead. He was really adamant about it, too. And I kept thinking, well, the unfair thing about this is that this is hypothetical for you.

Honestly, I think it seems kind of silly, and not to turn the Freudian analysis back around, but what intrigues me about the idea of whether or not it’s a few bad racist apples or if it’s all white people is that for white people, often, it’s the only time they have to worry about being stereotyped. And that the stereotyping against them results in maybe a change in their degree of social prestige when for black people or queer people (increasingly at this moment) or even other marginalized groups, the stereotypes can result in death, dispossession, and the eradication of their people.

When something racist or homophobic happens to me, Brandon Taylor, me personally with all of my privileges and my life experiences, I think, wow, that person is such a jerk! Or wow, that person is racist! Like, yeah, I have beef with the individual and don’t necessarily extrapolate to their whole lineage and their ethnic group. But also, when you’re looking around a program or an office or an institution and you see that no one looks like you and no one in charge looks like you and no one in this place has EVER looked like you when you know in fact that there are many people like yourself who have come before you in your field—then yeah, you start thinking that there’s something structural going on. And knowing what I know of this country, it’s hard not to imagine that it was on purpose to some degree.

9.Your perception of structural violence would seem to align you with Woke, but I get the sense that you're a bit skeptical of the Woke movement. Can you say more on this?

I think America has a very long and well-documented history of systematic and structural harm inflicted upon minorities and also white women. Often this harm has been expressed through exclusions from civic life or access to basic things like food, utilities, and in some cases, freedom itself. There is a reason that so many class issues in America look like race issues or gender issues, and it is because this country loves to create underclasses according to certain systematic biases. It’s the only thing this country knows how to do with great efficiency. Is that Woke? I thought that was just history.

What I am skeptical of is all the identity profiteering we saw flourish during Obama’s second term and during the first Trump presidency, eventually reaching its zenith during the pandemic under Biden. A certain strain of Tumblr mindrot really got into the cultural groundwater. That I find really tedious. But I find any kind of infantilizing tedious.

I used to joke about how DEI Twitter would pay for its crimes. Before we got into the current era where “DEI” is just a byword for nigger. What I meant back in 2020 and 2021 was that I was sick of the corporate enshrinement of liberal sympathy toward whatever they imagined a black person’s life to be like. It had its own set of baked-in racist assumptions about blackness that eradicated any potentiality for actual black subjectivity. Which is what the corporate world does. I experienced this in Academia, which is itself just another corporate space. There were all these “initiatives” for POC and “black” science students, and they made all these assumptions about my life experience and it was like, “oh, wow.”

I had my run-ins with the “Black Excellence” brigade or as some people used to call them the “Blavity Blacks.” Really kind of bourgeois “I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams” nonsense that trafficked in the same racial stereotypes white people were trafficking in, toward the same goal, ultimately, which was marginalization within these white spaces. In my more paranoid moments, I thought of it as being a PsyOp to make us pigeon-hole ourselves.

But I am also deeply skeptical of the reactionary conservative black media types. They’re basically the “they didn’t know I was in first class too” of the black intelligentsia, and even worse, they’re just doing it for money! It’s all very dire.

If that makes me Woke, sure. But I also think a lot of attacks on Woke or “Woke” in quotes is just a method of ego rehabilitation in the face of the wounds certain people took during a decade of assaults on their social primacy from SJWs. In short, they’re all just reactionaries.

10.In spite of moving away from science, there does seem to be something scientific/analytical in your writing — at least in a way of kind of surrounding questions and seeing them from multiple points of view. Is that fair?

Totally fair. I learned how to think when I was in science, and science is in many ways just a mode of inquiry. The same as writing. That was a real breakthrough for me. When I stopped thinking of science and writing as these independent processes and started to consider that they are both methods of discernment. And, really, they are the same method of discernment. When I set out to write, I am always trying to better understand what it is I am seeing or feeling. As I revise, I am updating my theory or my running hypothesis, whether I am aware of it or not. I think part of my process for better or for worse is to take nothing for granted and to work very hard at trying to create plausible explanations for what happens in a story. All as a means to explain my experience to myself.

My writing is driven by questions. Who are these people. What do they want. What do they need. What does this mean to them. Or to this person. And then I do that for every character in the piece so that I come to a more robust sense of the full complications of things. It’s the same with nonfiction or essays. I’m just trying to get to the bottom of something. Following one idea to the next to the next. And maybe I come away with an answer. Ideally, I come away with a better question so that I can go back and refine and get closer to something true or something that feels coherent to me.

11.I really appreciate the point you're making that all literature has an ideological, or political basis — at the very least, a point of view — and that 'art for art's sake' is basically stupid. Can you say more about that position and about the kind of pushback you get when you make it?

I do think art for art’s sake is kind of dumb, but I didn’t always think that. Maybe I will change my mind again in five years, who knows. I do care a lot about subjectivity. I care a lot about an individual’s ability to express their own particular subjectivity through language freely and carefully chosen. But I also think that the de facto liberalism of Anglo-American literature is kind of a PsyOp

A lot of people say that this is the CIA’s fault and the rugged American individualism that we exported during the Cold War in the face of the harsh, dehumanizing un-artistic socialist realism of the Soviet Union. I don’t blame the CIA or the Cold War. I blame liberalism, and if we’re keeping it buck, humanism.

“Art for art’s sake” is a political slogan that aspires to the status of moral credo while pretending to be totally apolitical. It is such a sneaky and dishonest way of saying nothing! I understand it as an aspiration, but the aspiration still arises out of a political status, which is the status of having ignored the material conditions of your time. I too would like to be a Saint, but declaring myself one does not make it so.

What turned me off from “art for art’s sake” was that I began reading criticism for the first time in my life. I felt like I didn’t know anything about literature despite having written books, so I decided I would figure out how to talk about literature in an adult way. My friend

gave me a stack of books to read and I went away and spent whole days just reading both critical texts and also histories of American literature.What became clear immediately from reading On Native Grounds by Alfred Kazin or Love and Death in the American Novel by Leslie Fiedler was that the arguments people were having on Twitter about whether “all art is political” went back a long time, and I’m talking, like, to the beginning of literature itself. The other thing that became clear to me was that all work had an ideological basis. Even Jane Austen, whom I loved and worshipped, had an ideology.

Last year or so, I went on a deep dive reading Lukács and Jameson to figure out why the socialists hated my books so much and were always bullying me on Twitter, and I suddenly had all this language to talk about the ideas in books. But also the form of books. I could suddenly see all of these connections between the material conditions and the work that arose out of those conditions. All these writers who were going around saying they had no ideology in their work were revealed to me as people who maybe just didn’t realize that the ideology governing their work was a strain of liberalism. And that it was clear to anyone paying even the slightest bit of attention.

I think it’s made me a better reader and a more thoughtful writer and critic. But it also means I clash with people I formerly agreed with. Which is not so fun sometimes.

12.The point you're making here seems to tie into a broader critique you have of the state of contemporary fiction. You write, "the contemporary un-novel has none of modernism’s or postmodernism’s desperate crisis of faith." Is that basically the problem — why so much of contemporary fiction is so tepid? That it lacks a moral compass and point of view, and everybody is just flotsam on the tide of neoliberalism?

I think a lot of contemporary fiction at the moment is totally lacking social texture. The characters are alienated and isolated, but the texts themselves are so mimetic of that experience that you can’t even…appreciate it or understand it. The texts lack any capacity to comment upon or interrogate the experience—they lack a dialectic. And so there is no potential in those works, no capacity for breakthrough. That’s why the dominant mode of contemporary literature is that of tragedy, because it all ends in dissolution, and not only that, but a dissolution that reaffirms the alienated experience.

This lack of potential, the lack of capacity for change, comes about because writers often don’t question or interrogate their worldview. They are setting out to create a precise and exact duplication of their spiritual and social condition. A strict, arid, dead realism. The work cannot get above or beyond that. It can only endlessly recreate the stolid material totality, and there is no…social, spiritual, or moral totality available.

In essence, it’s like watching a reality tv show but it’s the raw, unedited feed and there are no confessionals to comment in or set things in relation or context. Like, you might glean some insights into who these people are and what their relationships are, but ultimately, you will leave it having felt…what, exactly? There is no impulse toward integration of phenomena into experience, into meaning. It’s all arbitrary.

And, yeah, my pet theory is that is because they think recreating their spiritual condition is a sufficient engine for a novel. Mere description. But as Lukács tells us, description does not set levels. It cannot put things into relation. For that, you need narration, or as Auerbach calls it, diegesis. And for that, you need a narrator capable of explanatory power or integration. And that is just not in big supply these days.

Instead, we have a surfeit of sensory description or we get Sebaldian flâneurs of the soul—but what people always forget with Sebald or Bernhard is that those narrators actually do work in service of integration. Now, it may fail. They may fail to come to grips with the thing that’s forcing its way out of them. They may fail to tell a coherent story or narrative. But they are trying to. They are talking themselves back into life and in doing so, capturing some of history. And I think, when people copy them, they copy the form, not the moral and spiritual intent that comes along with the form.

13.The reviews you write have been really awesome, but you say that you've been getting a lot of flak for them. Why is that?

Well, people don’t like me. For a whole host of reasons. Largely, they think I’m a fraud who has more attention than they think I deserve. And I should sit down and shut up and not speak out of turn about other, greater writers.

I also get flak because people disagree! I don’t want to live in a world where people don’t get shit for having opinions. I do think that some of the responses to some of the things I have written have more to do with people’s personal dislike of me or their dislike of me as a critic or their idea of me rather than the actual things I wrote, because, frankly, did they even read the piece or the thing under review? Probably not, they’re just mad about something I tweeted two years and now is their time to get a lick in.

But that’s part of having a public profile. That’s part of writing public criticism. I don’t mind. What blows my mind though is when people talk shit about me, and I respond and they’re like, “not cool, man!”

This one guy said something about one of my reviews, and the algorithm surfaced it in my following tab. So I replied and said, “You made an enemy today.” And people were so annoyed or mad that I replied to him. But it’s like, if you talk shit about me, yes, you are my enemy. That is how it works. Talk shit, get hit, playboy.

But I think people get anxious about that sort of thing because they think people with power will ruin their careers.

14.There seems to be a real problem with honesty in contemporary literary reviews. Why is that?

Not to get all “material conditions” about it, but I think it’s a few things. A lot of the book reviews that get published are written by writers who are not primarily critics. I think a lot of novelists and fiction writers should probably not be writing reviews because they have a very limited understanding of their craft or how a book works or should work or how it’s in conversation with its tradition. They are in no position to evaluate the book under any metric except whether or not they personally enjoyed it. They have no critical faculty. What you get often is a review that says, “Hey, I liked it” or “I liked it except this one bit.” Or it’s a summary plus a line of “go out and buy it!”

Because while these writers may not understand their craft—despite writing very good books themselves, I should say—they understand perfectly the reality of how much a book review in a place like the NYTBR can help. And they understand that the book review is a useful commercial implement. They adopt this attitude of do no harm. It’s hard to fault them for that. They aren’t trained critics or primarily critics. They are writing about the book as a “reader.”

So there’s that.

Then there’s the fact that there are just so few spots for reviews. Hard to make a living on it. So the people who do have the expertise, right, are fewer and farther between. There are no incentives to acquire a deep reading base as a critic because most of that is going to be cut for space in a place like the NYTBR or WSJ or a short piece at the NYer online. So the reviews tend to function more as cultural criticism or trend pieces rather than literary criticism that points back into literature itself. Or the reviews function as more about the aura surrounding the piece under review. That’s frustrating, yes. But that’s just the nature of things in non-specialized publications. That’s why small magazines, journals, and places like LRB, LARB, Cleveland Review, Chicago Review, and of course, Substack, are so important.

It's my hope that these places continue to grow and thrive and to create an audience of readers who hunger for smart writing about writing. Because that will make the writing better, I think. Maybe I’m an optimist. But I say, make even more magazines where people can talk about literature as literature rather than as a backdoor into a cultural trend piece.

As for honesty, I don’t know. I think that’s maybe a misnomer. I think people are being honest. I just think that there’s very little space for nuanced opinions. And I think that the kind of environment of reactionary pans of praised books is equally dishonest. In both cases, you have works getting judged on the basis of things that have nothing to do with the work itself. Negative isn’t necessarily “honest” either.

15.And I assume part of the problem is that if you're a successful writer, it's bad form to criticize the other members of the club? Which is why it was so refreshing when you called Creation Lake a "sloppy book" — and then provoked a mini-war with Rachel Kushner's husband. Is the calculation successful writers make that it's just not worth it to say what they really think and then have an awkward moment when they run into Rachel Kushner (or her husband) at a party?

Certainly, that review made aspects of my life awkward in ways that I had not foreseen. It also told me things about certain of my relationships that I didn’t know before. There was this whole…social fall out from that review that I just didn’t see coming, frankly.

I got a review assignment of another novel written by someone in my relative sphere. And I was really nervous about filing it because any negative thing I say in the review will be read as a personal attack or a vendetta or whatever. Not even by the author, but by the social sphere and the internet. And then I’m on the hook for what other people will imagine this person will feel when I write about their book, like that’s crazy. And it’s like, I believe people have a right to feel pricked and criticized when they read criticism of their work. I am human! I know the feeling!

So I am anxious about this forthcoming review, and in fact, I think maybe I shouldn’t have taken the assignment. But then, it’s like, am I not allowed to write about my contemporaries? And it’s like, of course I am, but sometimes there are consequences.

I can’t speak for what other writers say or do. But for me, the calculation has changed a little bit over the last year. I think I used to review writers and I didn’t think about the social fall out because I was living in the Midwest and when would I ever be in the same room as these people? But now, I am increasingly in the same rooms and at the same parties, so maybe I should think a little more about this. But wouldn’t that be depressing? To pull your punches? I respect literature too much. I respect these writers too much. But also, that respect sometimes means I get whacked, and that’s okay.

Ultimately, I guess, I am okay with the consequences of my actions. I just didn’t know to look for them. Now I do.

16.I get the sense that you're kind of controversial, but I can't really figure out why. Is it just this? That you're willing to be more honest in your reviews than other writers?

I think it’s simply that people think I’m a fraud, lol. I think that’s it. I have more than they think I deserve and I should have less and I should speak less and take up less space and leave more room for all the other people who deserve more than I do. And who are better than I am because all I did was go to Iowa and get a book deal, etc, etc. They’re annoyed because they have a fiction about my life. Or maybe they just don’t like me. I don’t behave how they think a serious writer should and so I am therefore a poser and a faker as opposed to someone who just…doesn’t know how a serious writer should act. I never have.

But I am not as controversial as my friend Garth. Now there’s a name that provokes whole segments of the internet for reasons beyond my understanding. He’s so nice.

17.You've been a bit critical of Substack, or of Substack's potential to be a platform for meaningful writing. As I think you know, I'm a Substack fanatic and disagree with you. Can you explain your position a bit?

I have been critical of Substack Notes. I’ve been on Substack a long time, and I credit it with my development as a critic and an essayist. It’s a been a wonderful platform to write on. But Substack Notes introduced me to a contingent of people on this site that I find deeply annoying in a way that made me want to delete my newsletter and never come back.

I think as a social space and milieu, Substack is filled with reactionary and paranoid thinking. Particularly about publishing and the media. There is such a dweeby contrarianism governing a lot of the writing here. Which makes sense. It’s a place where people who have been excluded from various other social and media spaces can build an audience and talk about the things they want to talk about. It’s very zine-y. It’s very punk rock. Very democratic that way.

But it also generates a ton of bile. Every time I open Substack Notes, it’s a bunch of dudes and one really annoying woman talking about the fix of contemporary publishing. It’s like the annoying materialist Marxists on Twitter or the fatally woke mob of BlueSky, but on here, it’s just careerist bitterness masquerading as superior aesthetic judgement. Like, truly, a noxious atmosphere for me personally.

I hate it. Genuinely. I do. And I think the day they introduced that platform is the day they signed Substack’s death warrant.

But as for Substack as a platform for meaningful writing. Sure. I don’t think that’s inherent to Substack. You could get that on almost any newsletter platform. I think what Substack fanatics ultimately value is not the writing per se. What they value is the social dimension that seems attached at least nominally to the writing.

What I value about Substack is ultimately my relationships with Hamish and the tech team, who have been really, really, really generous and kind and helpful to me. They’ve made accommodations to the site experience to make this place, like, usable for me. And if I ever need anything, I just reach out, or they reach out, and they help me. And that to me is so rare in an era of platforms and social media tech guys. Like, the Substack guys seem to really care about their writers and their people. They seem to care about the experience on this platform. And I think that above anything else is probably why I stay. I am very loyal to Hamish and the rest of the team.

But Notes is a chop. Though I did mute several people and that has drastically improved the experience.

18.Let's see if we can make you more controversial than you are. Who are five contemporary novelists/writers you really admire?

My taste is all over the place. Scholastique Mukasonga, who has a new story in The Yale Review. Every new Mukasonga story is cause for a holiday in my life. I don’t even remember how I came across her. Just that her work made me feel so…strange. Like these weird, dark dreams. She makes me feel how Borges makes some people feel. David Szalay is a genius, and his recent novel Flesh is the best book I’ve read all year. It should win the Booker Prize. It won’t, but it should. Colin Barrett is such an incredible writer who renews the story for me with every story he publishes. Karl Ove Knausgaard because he is writing the epics of our time. I don’t care. They will never make me hate him. We will look back at him and think of him as the Roger Martin Du Gard or Galsworthy of our time. But weirder. And Patrick Langley. I read everything he publishes. EVERYTHING. I LOVE HIM. Such a sublime, strange writer. He should be incredibly famous.

19.And who do you think is overrated?

NICE TRY. Is anyone overrated? There are, like, no book reviews anymore. Who is doing the rating, like, lol. Be so serious. Overdiscussed? Overlitigated? Overscrutinized? I think Honor Levy, when that book first came out, was a bit overdiscussed and overblogged about in a way that felt kind of uncharitable and unkind to a young writer. Sometimes, the kindest thing you can do is give the writer a little space, a little shadow in which to find themselves. And I think having every corner of your work blasted with X-Rays for six months straight is a little cruel and unusual. But I feel that way about all the Dimes Square and alternative-lit people. Like, leave them alone. Stop talking about them. Let them work. Away from attention. See what grows out of it.

Or maybe the attention is the point, I don’t know. But I just thought that was kind of brutal and I would have died had it been me. It seems like the only way publishers know how to market books, especially first books, is as phenomena. Like, THE FIRST OF A NEW ERA, THE OPENING OF EPOCH, etc. What you then get is a ton of attention irradiating these early career writers rather than a cool, dark channel in which they can work and experiment and be strange and build authority over the length of a career. In that way, I think attention is kind of a death sentence.

But, I mean, again, there are no reviews and no place to promote books, so it’s hard to fault the publishers for doing what works, even if it’s at the expense of the artists they’re trying to create.

20.I think what I like the very best about you is that you have this maximalist vision of the novel — that you want to "bring back all of what a novel can do." I think what you mean isn't a Make The Novel Great Again traditionalism but more of just coming to the novel with high ambition, as opposed to producing what Joyce Carol Oates calls “the wan little husks” of contemporary fiction. Can you say more about the vision of the novel that you have in mind?

I think when people hear or use the word maximalism, they are imagining a kind of amusement park of prose and event. A spectacle in prose form. I don’t know that my vision for the novel is maximalist in style or mode as most people would imagine it. But I’ll just speak from my own experience here.

I worked hard at a novel draft for like five years on and off, but I just couldn’t bring it off. Part of that was that I wanted it to be at this almost Tolstoyan scale or Dickensian scale. I wanted the book to be about everything, but I couldn’t figure out how to do that with my inborn narrative instincts, which veer toward the Chekhovian, let’s say. At heart, I think I am someone who stages drama within small confines and excavates rather than lays claim to the totality of the social surface. So all of my novel-writing instincts were governed by that impulse. I just didn’t have the tools or the know-how to write the kind of novel I wanted to write. I didn’t even know how to describe the kind of novel I wanted to write in technical terms.

But then I started reading Lukács and Jameson, and some stuff clicked. One thing in particular was that I was starting my novel in media res and I was sticking very close to mimetic reality in a kind of cinematic mode. I wasn’t letting the book be a book. And I realized that, one, I needed to start over fresh on a new project, one without all the baggage. And, two, I needed to like…make the prose less…efficient. Less cinematic. Less dutiful to the governing ideas of contemporary fiction.

My agent and editor had a few rounds of comments where they were wanting the book to feel more urgent. To move through some of the dicusrive passages more swiftly. They wanted swiftness. And I’d write back to them and say, no, the slowness, the unfolding of thought, all of that is necessary because the book needs to remind you that it is a book and that you have to read it. I wanted to bring back to the novel some of that capacity for deep engagement. And not to apologize for it. Not to make it swift or efficient.

At the same time, you don’t want to waste people’s time. You don’t want to be indulgent, so I had this task of writing and rewriting, trying to take stuff that was boring or dead or dull or pointlessly visual, but also stuff that was just…”smart writing.”

The other thing is that my editor wanted me to take out a couple passages where the narration seems to slide away from the main character and toward other people. Where it essentially seems to enter into the experience of those people. And he said that it was just kind of unnecessary, but I told him that it was actually deeply necessary for the novel’s democratic project. That the book which is so much about faith and empathy and mediation and expiation, grace in the contemporary moment, must be capable of demonstrating what happens when you really consider someone else’s life to the extent that you are, for a moment, almost standing in their shoes, in their place. So those passages had to stay because they were, to my mind, the whole point of the book. The whole book builds to such moments.

But I could see his point, right, like, it’s in the way. It needs to be trimmed, etc, etc. I think a lot of books today go out having been trimmed in the wrong way or trimmed too much. There are a lot of novels today which apologize for being novels rather than film treatments. If I have any goal for my work moving forward, it’s to write novels. Unfilmable novels that you have to read to understand. No shortcuts.

And I will also say that part of that for me was bringing back the social texture to the American novel. Lot of novels about people in tall towers who don’t speak to anyone or go outside. Lot of loser fiction. By which I mean, fiction about social losers but the formal failure of those novels is ultimately that we cannot appreciate the extent of the character’s social failure because the author has failed to put them in a society. I wanted to write a book that takes place in a society. In relation to the other people. If anything defines the American novel these days, I would say that it's a lot of loser fiction unfolding without any social texture. Even books about families lack real social integration. It’s bleak. The Europeans, the Brits, the Irish, the Latin Americans, the Africans, and Southeast Asians. The best loser fiction, I think, comes out of Japan, China, or Korea, where you see very clearly how society creates social losers and how those losers struggle with society and with their communities. But in America, it’s just…a loser in a Beckettian space talking to himself.

My goal, I guess, is to open the door again. To let people back in. And to capture a character in the midst of a social totality.

I like that he's open to criticizing other writers, but he also criticizes himself.

I tend to dislike fiction that seems to know the answer. I remember reading a quote, maybe from James Baldwin, that went something like, "When you sit down to write you have to forget you know anything." So absolutely show how society makes someone into a loser, but don't allow yourself to think, "I know how society should be set up to prevent this." When I can tell a lot about a writer's politics from their writing, I have noticed that the writing is usually bad.

Great interview. My two cents is that I wish Taylor, who seems so profoundly liberal in his energies, would stop bashing liberalism as though it's only its most superficial manifestation. The guy's such a liberal in his bones, obviously.