His Struggle

On Keith McNally's Memoir 'I Regret Almost Everything'

Dear Republic,

It’s Travel Week here and who better to grace us with a piece but the king of Substack journeys Blake Nelson. If you haven’t read the immaculately-written sketches from past and present over at Travels to Distant Cities, do yourself a favor and binge-read. Alongside the portraits of places, you might spot an appearance from Basquiat or Courtney Love, and in this piece Anna Wintour. Blake goes back to mythical 1980s New York to review Keith McNally’s memoir and the origins of his legendary restaurant Balthazar.

-ROL

HIS STRUGGLE

In 1986, I moved to New York, and got a busboy job at a very cool nightclub in Tribeca. I was lucky to get such a job. This was at the height of the 1980s New York nightclub culture, made famous by various movies and books. Bright Lights, Big City being the most obvious one.

When my club closed, my manager suggested I apply for a job at the new Keith McNally restaurant.

I had heard of Keith McNally. He and his brother Brian were the two British restaurateurs—still in their twenties—who had opened Odeon in 1982, the hottest restaurant in New York at the time.

McNally then opened Nell’s, which was considered the hottest nightclub in the city. And the hardest to get into. Though lines of unworthy aspirants didn’t mind standing outside the velvet ropes, where they hoped to get a glimpse of Sting, or Madonna, or Johnny Depp.

Keith McNally was on a roll. The New York Times called him: “The man who invented downtown.”

*

To apply for the job, I went to an address in the East 20s and found myself in a room surrounded by New York’s top bartenders, hostesses, wait-staff, etc.

An energetic young man sat at a table. That was Keith McNally. There was a reverent silence in the room. Everyone was basking in the glow of his presence. And desperately hoping to be hired.

I didn’t get the job. But I remember the way people looked at McNally. He was like a rock star. But better. Because New York restaurant people were smarter and more sophisticated than rock stars.

The McNally brothers were above rock stars. They were stars in a social sphere that I—as a newbie New Yorker—was only beginning to understand.

*

Keith McNally is now in his seventies and he’s written a memoir, which has helped me understand a lot. It also made me wish I spent more time in his restaurants.

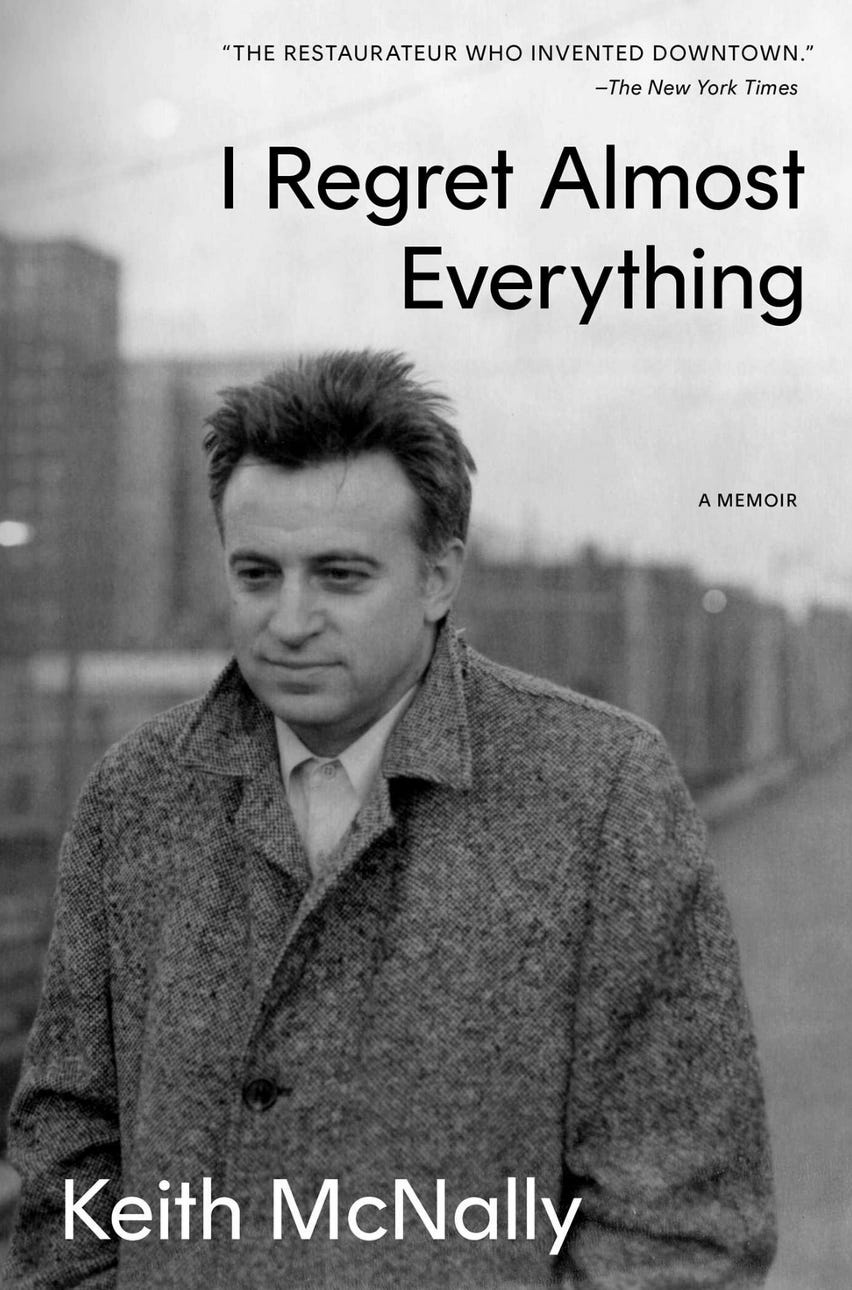

The book is called I Regret Almost Everything. As the title suggests, it’s primarily a confession. Besides telling his life’s story, McNally details his many troubled relationships and various other human failings.

He definitely wrote the book himself. It is not a polished celebrity memoir. It’s one person’s search for the truth about his life. Right up to his recent debilitating stroke and the suicide attempt it provoked.

*

McNally was born in a working-class family on the East End of London in 1951. He mentions being “working class” a lot. But his parents were both extraordinary people, in their way. As were his brothers, who are initially portrayed as London tough-guys, but who were clearly talented and capable, much like Keith.

Which is not to say McNally wasn’t “working class”, but his social class seemed to have no negative effect on his work life, or his social life, or his love life, or his ability to raise large sums of money.

*

At sixteen, he graduated from high school and began working at a Hilton hotel in London. A film producer spotted him and within weeks he was acting in films. (Get used to this. This is how McNally’s whole life goes.)

He then began a romantic relationship with Alan Bennett—a major English playwright of that time. Through Bennett, McNally was introduced to the highest levels of the London theatrical community.

Still a teenager, Keith acted in a BBC production seen by millions, but eventually decided that acting was “frivolous”, and then hit the road for nine months, following the hippie backpacker trail to Kathmandu.

Returning to London, he continued to work in the theater and then decided to emigrate to the US and make films.

He arrived in New York in October 1975 (age 24) where he got a job as a busboy at a posh Greenwich Village restaurant. There, he was quickly promoted through the ranks to general manager. This took all of five months.

As general manager, he hired staff, dealt with mafioso types and befriended a young customer named Anna Wintour, a friendship that included the future Vogue editor flying him to Paris occasionally to hang out.

So yeah. He was a man on the move. People liked him. People believed in him. He seemed destined for great things.

His brother Brian came over from London, and the two of them opened their first restaurant, Odeon, in 1982, which, from the moment it opened its doors was a smashing success.

*

Helping McNally create Odeon was Lynn Wagenknecht, whom McNally originally hired as a waitress at the posh Greenwich Village restaurant. The two began dating.

Wagenknecht was typical of his girlfriends: a stunning midwestern beauty, a recent Stanford grad, with an Iowa MFA. She had moved to New York to become a painter, but ended up marrying Keith instead.

With Odeon doing so well, McNally, his wife, and his brother decided to open more establishments, including Nell’s which became the iconic New York nightclub of the 1980s. Another restaurant, Indochine, was also a huge hit.

*

The memoir goes into detail about McNally’s methods for creating his unique establishments. We learn about lighting, design, layout, menus. Who he hires. Why he hires them. How to incorporate a sense of humor into a restaurant, and maintain a lightness and spontaneity.

To furnish these places, he flies to Europe or drives to New Hampshire to find just the right vintage mirror, rustic door, or wrought iron railing.

Having been to several of his restaurants later in my life—some of which I didn’t know were his—there was always an unmistakable aura, a sense of peacefulness, glamor, and intelligent design.

Keith McNally can literally be considered a genius at creating restaurants/bars/nightclubs. He has a vision. And then he creates it. And it is so well constructed that almost no outside interference can affect it. You are inside his world. And it is a very pleasant place to be.

*

But I Regret Almost Everything also focuses on the negatives of his life. The things he regrets. His bad qualities. The consequences of his bad decisions.

McNally is very hard on himself. He thinks he was a bad husband. He thinks he was a bad father. He regrets spacing out sometimes when people were talking to him. He probably had more friends than he could give proper attention to.

But really, isn’t that typical of any highly-productive entrepreneur?

Other shortcomings: He was a workaholic (obviously). And an autodidact, having not attended college. Though beloved by many, he did not always get along with those he was closest to. He eventually split with his brother, who took over Indochine. And when he divorced his Lynn Wagenknecht, he gave her one of his restaurants as well.

Probably the worst of his offenses involved the daughter he had with Wagenknecht. She became severely depressed in her early-teen years and was admitted to a mental hospital. He never visited her. He basically ignored the whole situation. So yeah, that’s pretty bad. That’s definitely regrettable.

*

Also, he really likes women and they really like him, so there’s a lot of carrying on in that realm. He beats himself up about that, though he clearly cherishes these encounters, and probably regrets them only in principle.

And of course, as times have changed, he now understands that a lot of his sexual and romantic adventures were inappropriate, according to our more enlightened views of sexual power dynamics. “Dating the waitress you hired,” being a typical example.

But of course, dating that waitress—Lynn Wagenknecht—led to marrying her, which led to her co-creating and eventually owning some of those legendary restaurants, which she apparently had a talent for.

So it worked out pretty well for her—not counting the millions of dollars she received—it was probably better than “becoming a painter” which was her original plan.

*

At one point, McNally’s various restaurants were grossing $80 million a year. He owned multiple homes. He traveled the world. He was internationally famous. Much of which he finds unsatisfying. There’s a vague regret associated with his many accomplishments. As sometimes happens to very successful people.

Still, he continued to open new restaurants. He married again, to another beautiful woman (a customer, he met at one of his new restaurants). With her, he had another set of children.

Needless to say, his life grew ever more complicated. There were inevitable setbacks. And as time passed, some of his new projects were less successful than the string of hits he enjoyed at the beginning.

So these were the things he regrets. Personally, I don’t know why he regrets them. How could his life be otherwise? This is what happens to people who succeed at this level.

*

As for the people he “hurt”, I mean, if you don’t want to exist in the gravitational field of such a dynamic person, you can always leave. And if you make the mistake of marrying him, you can always get a divorce and take half his money.

The fact that McNally felt obligated to write this book, and apologize to all the people he “neglected” or “was unkind to” or “had sex with when he was their boss” seems to be a product of his Boomer sensibilities.

Throughout the book, you can tell McNally feels obligated to abide by the attitudes and morals of our current time. Many of which are skewed against men like himself.

If he wants to clear his conscience, that’s fine. But I have to say, I don’t entirely buy it. This soft, sensitive, apologetic soul he presents to us in this book, might not be representative of his entire personality.

When he was 35 he was one of the most celebrated figures in New York. Are we supposed to believe he wasn’t a little sociopathic at times? He didn’t have to screw people over occasionally? He never used his status and power for non-virtuous purposes?

I suspect Keith McNally was one tough bastard when he needed to be. He was, as he keeps reminding us, “working class.”

*

Anyway, I really enjoyed this book. Even the details about his recovery from his recent stroke and the suicide attempt are told with engrossing honesty—all the more so once you’ve got the groove of his personality and his unpretentious writing style.

And I would especially recommend this book to anyone who ever worked in a serious restaurant or has eaten in one. You will enjoy hearing how one man brought that experience to the level of fine art.

Blake Nelson writes TRAVELS TO DISTANT CITIES at Substack.

Blake has perfected the travel narrative. Always great to read his work.

Well written. I am also struck by his regrets about not paying greater attention to the people he loved and cared for. However, from having worked in restaurants I know they are a lot of work and all consuming. Even a basic restaurant is like that. He must have worked very hard, consistently, to create what has. I guess it's true what they say - attention is the rarest form of generosity. Hard workers give their attention to work and then later realize that they should have given more attention to those they love. ❤️