Dear Republic,

We are proud to run this piece. The prompt was to ask Paul what it’s been like, over 50 years, to talk to people about the Vietnam War.

-ROL

TALKING ABOUT VIETNAM

What has it been like over the last fifty years to talk to people about Vietnam? What can people who were there tell people who weren’t? Well, before we talk about it we have to know about it. Here’s how it was for me.

Imagine a massive column of young men walking down a wide road. They are not an army. They’re dressed in slacks, jeans, bell bottoms, colorful polo shirts, pin stripe shirts, loafers, sneakers. For four years they pass by, first by the hundreds, then the thousands. Most of their faces are thoughtful, some animated—talking, laughing, an occasional argument here and there. They are going somewhere, answering a call, and they share a deep-down vague sense that it will impact them in a big way for the rest of their lives. But how? Will it be good or…

Doesn’t matter. They are young, and young men must act; they must move forward. They arrive at a fork in the road, a Y intersection. The majority of them start down the left leg, the others down the right. The lefties and the righties will forever after be on opposite sides of many things in many ways. Some believe that this divide was bigger than the Civil War, and that it broke the country in half. In April of 1968 I joined those going down the right fork.

Did the Vietnam War really divide the country forever? Or did it just bring existing differences to the surface—the way Americans looked at their country, the world, and their place in it? One thing is for sure; everyone was affected, mostly young men, but also their fathers and mothers, their siblings, and their wives and children, if they had them. It came to my door when the U.S. government sent me a letter. It read, “Greetings, from the president of the United States…” I was drafted and would likely be sent to Vietnam. That massive group of young men who had taken the left fork were deferred and would not have to serve. Deferments were given to young men who were attending college, young men who were married and had children, young men enrolled in ROTC or the National Guard. They even had deferments for young men who were public-school teachers in poor Black neighborhoods. I seem to remember reading that one, maybe two, of the Rockefeller sons got that deal. When I search the internet today, nothing about that comes up. Strange...

At the time I was nineteen, but quite naïve. On a bright spring day, my father drove myself and a couple of my high school buddies downtown to the offices of the draft board at 401 North Broad Street in Philadelphia. There I was told to join a group of about fifty other guys standing around expectantly in the middle of a large lobby. An army officer approached and stood before us. He told us to raise our right hands and swore us in. Then he told the tallest and most eager-looking one among us that he was ‘in charge.’ He handed him a clipboard with everyone’s name on it.

I started toward my father and friends to say a final farewell, but the officer blocked me and said I should have already said my goodbyes. I gave a wave to my father and friends and then I and my fellow draftees left the building and marched, sort of, down Broad Street. The spring air was warm and muggy. Coming to the sandstone edifice of 30th Street Station, we entered and went down the stairs to where a train awaited us. We boarded and took our seats. The train rocked, clickety-clack, as we left the station. We moved at a sedate pace through the city, passing hundreds of little modest row-houses. Factories passed by outside the windows, some lit up, issuing white smoke from towering stacks, some abandoned with most of the windows busted out. Reflections of gentle hills of weeds and new pristine suburban developments crawled across the windows along with occasional barns and fields of hip high deep green stalks of corn coming up. We crossed rusting steel triangulated truss bridges with broad shallow sluggish, weed-patched rivers rippling below. We were mostly upbeat as we sat, talking, playing cards. But some guys sat alone with their thoughts, some with their little transistor radios pressed to their ears, the tinny strains of rock or Motown leaking out.

Night turned the windows black, and the general buzz of talk quieted, coming almost to a stop. I thought sadly of my family and friends and about how I would miss them, but I was already drawing comfort from my new friends. We were young and full of life, with our futures before us—some wonderful, some boring and mundane, some awfully short and tremendously violent. I never really thought much about the potential awful part. Whatever we were going into, we were going together, and that comforted me. I awoke when the train grew still and quiet. We’d arrived at a rail stop near Fort Bragg.

Basic Training was an eight-week blur of exhaustive physical training—run, dodge and jump course, hand-to-hand combat, five am barrack inspections, pushups, low crawl, live fire obstacle course, ten-mile hikes. We sat in bleachers under the hot North Carolina sun, listening to boring lectures about what a sneaky, lowdown adversary ‘Charlie’ was, how to fire, disassemble and clean an M-14, how to carry a wounded comrade, how many and what kind of malaria pills we would have to take, how to bandage an arterial wound.

We didn’t get much sleep, maybe five hours if we were lucky. A couple times we went to the enlisted men’s club—an ugly unpainted plywood faux-Polynesian bar with a palm thatch someone had crafted out of cardboard, set on a weed patch within a barb wire enclosure. We guzzled 3.2% beer and got to know our fellow soldiers. I can find a sad kind of humor in it now, but those brief interludes were wonderful, bits of heaven in a bleak, difficult period of my youth.

Then the first part in this great adventure was over. We put on our dress uniforms and marched smartly around the parade field for graduation. We were then bussed to an airfield and put on a jet, landing at Shreveport Louisiana to start part two—eight more weeks of Advanced Infantry Tactics school at Fort Polk. That involved going on pretend reconnaissance missions in the woods, familiarizing ourselves with the various infantry weapons—50 caliber machine gun, TOW portable missile launcher, M-79 grenade launcher, 45 caliber pistol, and the M-16 automatic rifle we would be issued when we got to Vietnam.

When it was over we got two weeks’ leave. After that came part three, our ‘tour of duty.’ We reported to Fort Lewis, Washington State for our flight to Vietnam. What followed over there became fodder for my book, Carl Melcher Goes to Vietnam.

Here's a little snippet from that:

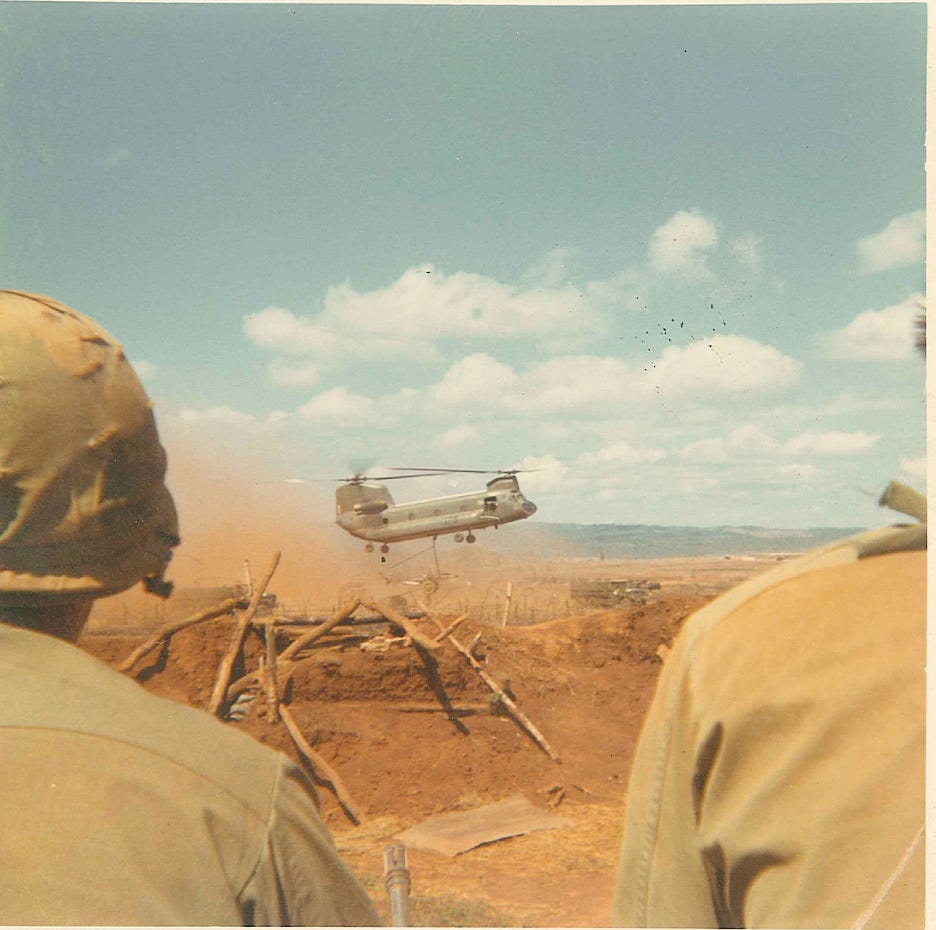

… we were to be helicoptered out to the boondocks, closer to the enemy. I heard the choppers approaching, their blades going, thock-eh-ta-thock-eh-ta. A few moments later the first one settled down like a duck on a pond, raising a storm of dust. One of the door gunners waved us forward and we ran, hunched over, and scrambled quickly inside. We crowded into the center, our knees pulled up under our chins, as far away from the open doors as possible. Then I noticed Beobee and Glock sitting calmly with their feet hanging out the door. I followed suit.

The pilot wore a helmet with a mike. After looking around to make sure we were all in, he eased back on the stick. The chopper shuddered like a washing machine on spin with an unbalanced load as we lifted a foot or so off the ground. We started moving forward and Glock and I broke out in ear-to-ear grins.

It was magic. With our feet dangling earthward and the wind whipping through the cabin, we climbed quickly to four or five thousand feet. Soon we were over the jungle, and from this height it looked like a green sea with mountainous swells. The pilots seemed like young gods with fantastic powers as they worked the various controls that kept us shuddering and swaying through the sky like a great metal bird. I would have given anything for the guys in the neighborhood to have seen this...

Beobee tapped me on the shoulder and pointed to a brown smudge in the distance. “There it is,” he yelled over the noise of the engine, “Firebase 29.”

The Firebase was slightly higher than the surrounding peaks. Its trees and foliage had been scraped off, giving it the appearance of a reddish-brown island in a sea of green. About twenty-five 105 howitzer artillery pieces were arranged around the perimeter, and I saw men carrying boxes full of rounds from a big pile over to one of them. Then the ground was rushing up at us as we came down, and the people down there turned away and covered their eyes as our chopper’s blades whipped up a storm of dust. I hopped off with the others and we ran behind a sandbag wall. The next bird landed before the wind from ours had died down and then they were both gone, the thock-eh-ta sound echoing off the hills as the dust cloud slowly drifted away.

Why did we get involved in Vietnam? Government think tanks said we needed to protect the democratic South from the aggressive Communists in the North. Then there was the domino theory—if Vietnam fell, so would Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. And the Gulf of Tonkin incident, when North Vietnamese gunboats attacked a U.S. warship, the USS Maddox. On the liberal Left side, people believed we simply had no business there, that it was a civil war or a war of liberation. Some believed—with not much evidence—that certain American businesses, notably the oil industry, wanted to exploit the resources there, much like the United Fruit Company had in Central America in the 1900s.

At the time, most Americans leaned toward the government’s side of the argument. That would change as the war went on and on. But my relatives and friends mostly believed in the government’s stance. When I got to Vietnam, my buddies rarely talked about the politics of it. There might have been a comment here and there about ‘fucking draft dodgers,’ stuff like that, but what was the point? We were in it. During the lulls we soothed ourselves with grass and Hamm’s beer, and talked about home, sports, girls, music, and how ‘short’ we were, that is, how much time we had left in our ‘tour.’ Unlike WWII and Korea where the GIs were there for the duration of the war, we had to do 365 days and then we went home, our duty completed.

Back home, that other crowd of baby boomers who had taken the left fork in the road were living their lives—attending college, dating, going to rock concerts, sometimes studying, smoking grass and going to anti-war protests, an activity that was, perhaps, more social than political. You could meet lots of girls there and occasionally get laid. Some, however, got swallowed up by the hippie sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll culture. Years later when the war finally ended in 1975, those who went and those who didn’t would once again rub elbows as fellow white- and blue-collar workers, suburban neighbors, bowling club buddies, and social acquaintances. But that fateful decision we made remained deep within us. Over the years scar tissue formed, almost eliminating the pain. But it would flare up when triggered.

COMNG HOME. TALKING ‘NAM OR FORGETTING ABOUT IT?

When I was discharged from the Army in 1970, my parents never asked me how it was over there. They seemed to know that to bring it up would open wounds. And I was glad of that. I never brought it up to my relatives or buddies and neither did they. They seemed to know that I didn’t care to talk about it. Or maybe they got enough information from the nightly news on the three big channels—ABC, CBS, and NBC. Some correspondents—supposedly—covered the war from the air-conditioned bars in Saigon. Others put their lives on the line filming firefights in the elephant grass, and the Medevac helicopters being loaded with the wounded and body bags.

When I returned I was still in the throes of PTSD. During WWII, the military were aware of ‘combat fatigue.’ It was likely worse back then. But during the Vietnam era, there was no supervised decompression, no counseling. And I don’t recall ever discussing—calmly or heatedly—the morality or necessity of the war. The war just ‘was,’ like the economy or the weather. I was done with it and it was done with me. I returned to the job I had been working when I was drafted—apprentice blacksmith at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. I write about that in my so-far unpublished novel, The Fake Memoir of a Mid-List Writer.

Being an apprentice entailed performing a lot of menial tasks. Sometimes I spent days cutting ten-foot lengths of flat bar stock into smaller pieces. Sometimes I followed Brock around like his Sancho Panza, with a wheelbarrow full of metal stock and tools. Sometimes I cold-stamped hundreds of pieces in a dye. Sometimes I worked a drill press, putting bolt holes in those pieces. It was boring and I despaired of it. But I knew that as the apprenticeship went on, I would be exposed to a lot more interesting work and concepts. Blacksmithing was a craft, but a science as well. In our classes they covered the chemistry and physics of ferrous metals. And there would be trigonometry further on. I dreaded the thought of that because I had only taken one year of algebra in my freshman year of high school.

There were a few things about the job I really liked, especially the laid-back atmosphere in the mornings. We stood by our forges, waiting for them to come up to temperature, sometimes for an hour. All the journeymen discussed their jobs while their personal coffee pots percolated on white hot fire bricks. Most guys brought in bacon and egg sandwiches their wives had wrapped in aluminum foil for them and heated them up atop the chinks in the fire bricks. The aroma was wonderful. I usually went to the vending machines in the locker room and bought a cinnamon bun to warm up and have with my coffee.

These older men were quiet and serious, and I liked them. We would talk at these times. They were interested in my experience in Vietnam, but they were respectful and didn’t probe. I just gave them the condensed version—the part of the country where I’d been stationed, the fact that a grenade had temporarily put my leg out of commission, the fact that I’d recuperated in Japan, that sort of thing. They would tell me about other men in the shop who were vets, Korean War, and some from WWII. The guy that everybody watched surreptitiously from a distance and occasionally speculated about was Tony, an ex-Marine. Like me, he had been medevac’d off the battlefield in ‘Nam. But unlike me, he hadn’t had to complete all his time in the service; he’d gotten a medical discharge from the Marines for mental health issues. The guys called him Mad Tony.

After a couple months of trying, I had to quit. I just couldn’t do the straight 7:30 to 4:00 working-man routine while the whole world was changing fast and moving away from me. I wanted to be out and about to witness it, or, even better, to participate.

All during this time I discovered that the friends I had left behind had left me behind as well. The ones who went to college didn’t have much time for me. They weren’t shunning me; they simply had to conduct their new lives as students. They hung out with their new student friends, while I had my old high school friends—a couple of whom had served and a couple who had gotten deferments. We embraced the hippie ethos completely. For about two years all I did was work shit jobs—car washes, parking lot attendant, security guard—and get high: mostly grass and Boone’s Farm or Ripple. Occasionally, under controlled conditions, acid. Later, it was pharmaceutical pills and speed. I had a lot of good times, but they were wasted times and that wasn’t good. I had made it back from the killing fields of Vietnam in relative health, but I was having a hell of a time re-entering society.

My druggie friends and I talked mostly about hard rock music and all the hippie-type happenings in Philly—free rock concerts in Fairmount Park, Be-Ins, who had what kind of dope, what band was appearing at the Electric Factory, who was the fastest (not greatest) lead guitarist (hands down, it was Alvin Lee of Ten Years After), hippie chicks (sure like to ball). But we never discussed the war in Vietnam and my role in it. They never asked and I never felt any compulsion to talk about it.

A year and a half passed in a blur. Then I met a girl, Lisa, who changed my life. She opened my eyes to how I was pissing my life away. She and her suburban friends were wealthy. They were going to college and deferred, and they all smoked grass. Her next-door neighbor had a pool. I started partying with them. Most of them accepted me, but some were aloof; maybe the fanciful stories going around about Vietnam vets going bananas and killing people had something to do with that. They did talk about the war on occasion, mostly about the higher-up political chess game being run—Nixon, Johnson, Kissinger, FBI wiretaps, secret outreach to Vietnamese leaders on both sides. I didn’t give a damn about any of that and didn’t participate. They seemed to be sympathetic toward me, some likely seeing me as a victim. I didn’t see myself that way. I saw myself as lucky, having played the hand I was dealt and survived. They never argued about the war. It was all cerebral to them, some puzzle they wanted to solve, and none of them ever openly or aggressively attacked me for having served.

In 1971, Lisa and I drove down to Washington DC for the May Day protests against the war. I was divorced from it. I only thought about it when around others who were concerned and agitated. I wanted it to end, of course. A lot of guys like me were still being killed, wounded, or mentally fucked up over there. But I was skeptical that a bunch of people marching around with signs would change anything. Lisa, however, thought we had a moral duty to make our voices heard.

The May Day protest devolved into a riot. The Yippies, a bunch of freak agitators, rumored to have Communist ties, ran amok, shutting the whole city down. They goaded and attacked the police and National Guard troops. (Sound familiar?) And the police and National Guard troops retaliated by beating up anyone who even remotely looked like they were a part of it. Lisa and I saw people bloodied and in shock making their way away from the scene. So much for discussing or debating the war… 12,000 people were arrested and the war went on for another four years.

In 1972 Lisa encouraged me to register for classes at Community College of Philadelphia (CCP). (Two years later I transferred to Temple University and graduated with a BA in English.) At CCP, I looked like every other young white male student—bell bottom jeans, flannel shirt, untucked, long hair, mustache and/or beard. About a third of the students were African American, many of them sporting large Afro haircuts and red, black, and green African-themed clothing and jewelry. With the exception of one guy, a Navy vet who had been stationed on a carrier offshore during the war, nobody ever asked me if I had been to ‘Nam. I didn’t feel the need to hide the fact; it just never came up in conversation. That likely had to do with the demographics at CCP. We were predominately white and black working-class people, the common clay that the Draft Boards mined regularly. During my years at CCP I saw no protests or rallies there, although they were going on at a lot of the other campuses, many of them private colleges for rich kids.

I recently had coffee with a fellow writer and vet. He had been a helicopter maintenance technician during the war, stationed in Vung Tau, Vietnam, one of the most popular in-country R&R (rest and recreation) fleshpots. He hadn’t seen any action. His tour consisted of working on choppers from 7 to 4 and then going to restaurants and massage parlors.

I asked him what his experience had been when he came home in 1970. Same thing as mine; nobody asked him about what it was like, and he never brought it up. By 1971 his hair had grown longer, and he looked like everybody else. He was accepted to UC Berkeley, and while there nobody asked him about whether or not he’d been in ‘Nam. He said that there were a lot of ‘actions’ against the war—rallies, speeches, campus sit-ins, that sort of thing. He didn’t participate and neither did the actions hinder him. He did say that the rhetoric was changing, however, and that it was not only anti-war now, but becoming anti-GI. As evidence, one of the new chants was, “Ho, ho, Ho Chi Minh, the Viet Cong are gonna win!” He said the Berkeley protesters didn’t put much thought into what they were chanting, but it did have to rhyme.

When William Jefferson Clinton (a baby boomer) decided to run for president in 1992, his actions during his younger years became quite controversial and dominated the newspaper opinion columns, talk radio, and news panel TV shows. I do vaguely remember a few arguments with co-workers, friends and neighbors, but no shouting matches.

Bill Clinton had been deferred and went to University College in Oxford, England on a Fulbright Scholarship. While there he organized a Moratorium to End the War event in October 1969. Coming home, he ran for and became Governor of Arkansas. Eventually he was elected President of the United States in 1992.

To be fair, there were many on the right who also managed not to serve. The man who replaced Clinton, George W. Bush, another baby boomer, had never gone to ‘Nam either. Due likely to his father’s connections, he secured a position with the Texas Air National Guard. Thus deferred, he spent his weekends flying his jet back and forth over the flat brown mesas of Texas with never an angry bullet shot at him. His Vice President, Dick Cheney, garnered four student deferments and a fifth when he became a father. He also never had the pleasure of serving in wartime.

THE DAWN OF SOCIAL MEDIA. NOW EVERYONE HAS A VOICE

One of the first friends I made on social media was a conscientious objector. Born and raised in California, he objected to the war on moral grounds. He refused to serve, to be a part of the war in any way. Some guys who had gone to Vietnam would likely not have anything to do with him. But I didn’t have those feelings. He paid a price for his refusal to serve—doing time in a Federal Penitentiary. Although we corresponded on and off, we never discussed the war, never found a reason to. We were done with it, and it was done with us.

I met more people on the internet and found old friends. One of the things I’ve discovered about social media—and it’s both good and bad—is that it empowers the meek and the weak. People who would never speak up at a staff meeting or argue politics with friends or neighbors were now sitting at their computers, ripping other people ‘new ones.’ They were typing fire-and-brimstone diatribes and lobbing them at whoever, while growing armies of followers.

When Facebook showed up, it didn’t take long for all the anger and guilt about the war in Vietnam to show up as well. What resulted was not what I would call talk or discussion. It was more like angry typing to unseen, unknown, but hated, enemies. Yes, full disclosure… on occasion (and I’m not proud of it) I got in the fray, especially if it was late at night and I had been drinking.

During this time an old friend found me on Facebook. Richard had been a fellow Buddhist. (I got into Buddhism—an almost cult-like sect of it—for about 13 years, from 1973 to 1985.) During Vietnam my Buddhist friend Richard had had a teaching deferment. He had been against the war. We spent a lot of time together at our Buddhist meetings and other proselytizing efforts, but I don’t recall ever discussing or arguing about our choices during Vietnam. However, at some point Richard and I got into an on-line chat argument over the Barack Obama vs John McCain election. Our disagreement got so heated it went all UPPER CASE. Sadly, our friendship never recovered.

There was one time when the ‘Nam divide erupted, not online, but in my daily life. In August of 1990, I was working for a major defense contractor. Our project was behind and we were working overtime to catch up. There was almost no one else in the building. Vince had his little desktop radio on. Saddam Hussein had just invaded Kuwait a week earlier. To get involved or not was the big political controversy of the day. This night, more reports came in about Iraqi troops taking preemie babies out of their incubators in Kuwait hospitals and dashing them on the tile floors. Vince insisted that now we absolutely had to go in. I countered that the preemie story might be pro-war propaganda. (Turns out I was right.) Vince, who was roughly my age, had taken the left fork in that road long ago. Now he was almost foaming at the mouth, his canines becoming protuberant, shouting at me that we had to ‘blow them to pieces.’ Vince had opted out of going to ‘Nam, but was now implying that I was a coward for not wanting to immediately air-drop thousands of young American men over there. If not for the fact that we were working in a secured defense facility, festooned with CCTV’s and guard stations at all entrances, I think we could have gotten into a fist fight over it.

TIME LESSENS THE SENSITIVITY OF TALK ABOUT ‘NAM

Something happens to a man when he arrives in his sixties, his seventies. A realization emerges from the dull fog of his routine. Maybe it’s the growing paunch, maybe the prostate he didn’t even know he had in his 20s, 30s, and 40s. He realizes he only has one, maybe two more laps left in his race. He thinks about the steady pace and joy of work, now gone, the fact that his children, now grown, don’t call, that when they do come to visit, they seem distant and unrelatable. He thinks about that road not taken.

A couple of friends of mine who ‘didn’t go,’ are now curious. ‘How,’ they wonder, ‘would I have handled myself? Would I have done what was expected of me, or would I…’ I want to tell them that they would likely have acquitted themselves honorably, as most had. But they don’t know that. And they wish they did.

Some others appear to get off on the idea of war and combat. A few even wax heroically about how they would’ve ‘kicked ass’ if they’d been over there.

Now I’m old and living in a desert community. We have lots of sand and casinos, and elderly people, and quite a few of them are veterans. I occasionally see them when I am out and about, wearing their caps emblazoned with their unit names and insignia. Nobody bothers them or me. (In the San Francisco Bay Area that might not be the case.)

Hopefully we Americans have enough years ahead of us to heal. Maybe wise men and women will make war obsolete. Maybe not. Maybe it will take God coming down from his heaven to put an end to it.

In 1967 I was a young American. I was happy, carefree, and ignorant of the world. I trusted my government and believed they had our best interests at heart and would never lie to us or put us at risk.

Peace!

Paul Clayton is the author of a historical fiction series on the Spanish conquest of the Floridas—Calling Crow, Flight of the Crow, and Calling Crow Nation—with Putnam/Berkley. He has also published a fictionalized memoir, Carl Melcher Goes to Vietnam, with Thomas Dunne. It was a finalist at the 2001 Frankfurt eBook Awards along with works by David McCullough, Joyce Carol Oates, Amitav Ghosh, and Alan Furst.

All photos courtesy of Paul Clayton.

Highly recommend Paul Clayton's book Carl Melcher Goes To Vietnam. It's great storytelling that takes us to a place the USA would rather forget.

Nixon's body was transported to the Nixon Library and laid in repose. A public memorial service was held on April 27, attended by world dignitaries from 85 countries and all five living U.S. presidents. I remember asking myself, "Has everyone forgotten?" I hadn't.